We weave in and out of traffic, sprint toward closing subway doors and run up and down escalators, but in the end we usually end up at a bottleneck being forced to do what we were trying to avoid: wait.

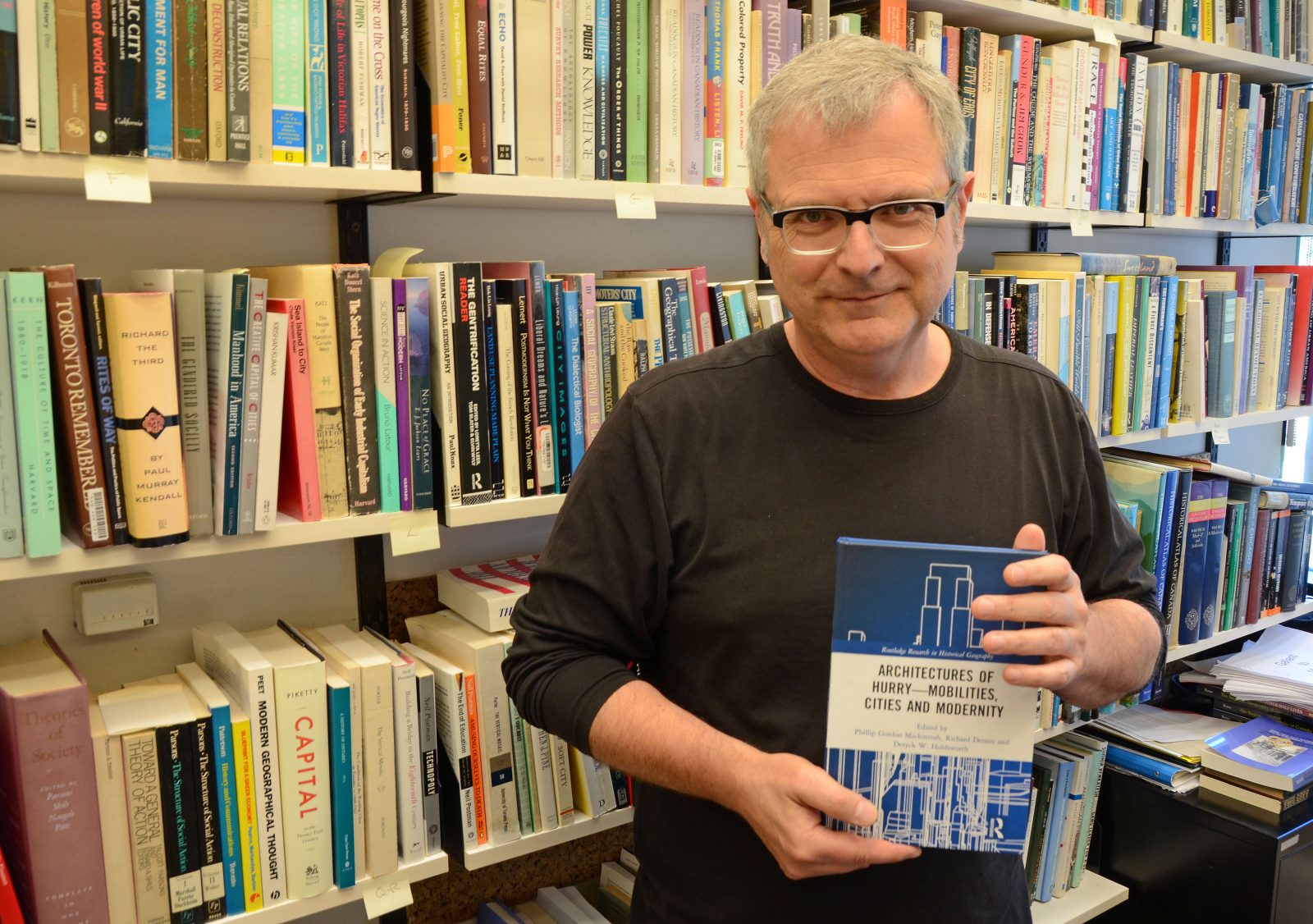

This is the central insight of Architectures of Hurry — Mobilities, Cities and Modernity, a collection of 12 historical essays co-edited by Brock Associate Professor of Geography and Tourism Studies Phillip Gordon Mackintosh.

The book examines the development of transportation modes and infrastructure as facilitators of hurry — as opposed to speed — in cities across the world, including London, Beijing, Buenos Aires, Toronto and Montreal, throughout the 1800s and 1900s.

The goal of this development was not only to increase the range, scope and speed of travel, but also to abet the modern urge to hurry, which often results in the opposite of hurry.

The various essays explore the evolution of transportation from horse and buggy to bicycles, automobiles, buses and subways, as well as the development of infrastructure such as street layouts, surfaces, rail routes and buildings to support new modes of mobility in a hurrying world.

There have been some unexpected innovations that helped facilitate travel. For example, one of the essays looks at the creation of a hotel industry in 19th century Montreal.

“This enables people to find home anywhere,” says Mackintosh. “You can now hurry around the world and find temporary shelter in any city. But this also means you’re waiting, often frustrated, in lines to check-in or check-out of hotels or airports, dropping off or collecting luggage, waiting for transport or transit.”

Another essay discusses the rapid appearance and disappearance of business exchanges in Lower Manhattan during the late 1800s.

“The buildings themselves live according to what geographers talk about as ‘geographical mobility,’” says Mackintosh. “We forget that many buildings have short lifespans, that the solidity of bricks and mortar can be fleeting. The only certainty is the land they sit on. Some buildings come into and slip out of existence with such remarkable ease, we can think of them as having a similar mobility as their occupants.”

Weaving the essays together is the central theme of hurry, perhaps the motivator of speed and efficiency. It reflects — and perhaps incites — our “pursuit of quality of life, convenience, comfort, power, security, consumption and accumulation,” says the book’s closing essay.

“We distinguish between speed and hurry,” Mackintosh says. “Speed is likely the implementation of hurry, which may well be instinctual, but is certainly part of the human geographical imagination.”

Mackintosh says the ‘hurry’ impulse that propelled cities’ interest in infrastructure development is still with us today. He says it’s fascinating that what we call “traffic generation” and “traffic volume” are measurable consequences of hurry.

“In North America, we knew over a century ago how to generate traffic. We chose to generate it with cars, but we could have just as easily generated it with public transit systems. For reasons good and bad, we didn’t,” he says.

This is probably because we don’t give enough thought to hurry.

“Everybody hurries, yet we rarely consider why beyond our immediate instrumental concerns. Part of our desire to hurry grounds to the urban capitalist imperative, but hurry isn’t modern. Hunter-gatherers hurried, so did early seed-sowers and classical Romans. Hurry predates capitalism and modern cities,” says Mackintosh.

We train ourselves to privilege our own hurry above others’. The result, he says, is that people caught up in traffic jams or line-ups become anxious and take out their frustrations on each other through road rage, swearing or other anti-social behaviours, increasing stress levels all around.

The phrase “Architectures of Hurry” comes from E.M. Forster’s 1910 novel Howard’s End, and was the inspiration for Architectures of Hurry — Mobilities, Cities and Modernity.

At one point in Howard’s End, the character Margaret Schlegel calls the modernizing London street, in the new automobile age, an ‘architecture of hurry.’ She worries that the only point of urban life is the accommodation of hurry.

Following their “Architectures of Hurry” conference sessions at the Royal Geographical Society in 2015, Mackintosh and co-editors Richard Dennis, Emeritus Professor of Geography at University College London, and Deryck Holdsworth, Emeritus Professor of Geography at Pennsylvania State University, were approached by an editor from Routledge Publishing who thought that a collection of essays exploring ‘hurry’ would make a good book. The 247-page volume is now available in the James A. Gibson Library.

Story from The Brock News

June 25, 2018