This week’s post is a long read by history student Sean Thomas, who spent a week living like an American Revolutionary War soldier.

Sean initially wrote this piece as an assignment for HIST3P31 “Historian’s Toolbox,” taught by Professor Colin Rose.

“The assignment was to live historically, in one of several time periods, and to write about what that experience was like and what was learned from doing it,” explains Sean. ” I chose to live like an American Revolutionary War soldier.”

We hope you enjoy reading about his week as much as we did!

"Soldiers at the siege of Yorktown" by Jean-Baptiste-Antoine De Verger is a watercolour sketch showing American soldiers in 1781. (Source: Wikimedia)

Living historically as an American Soldier during the Revolutionary War was no easy task. My method before I began my seven day experiment was to read all of General Washington’s “Rules of Civility” and watch the video on Vice and find a middle ground that I believed would be possible while still attending school.

The rules were fairly easy to adapt to school life, since most of them were just one hundred and ten ways to say be polite. The more difficult part was the actual daily routine.

The day before I set out to live historically I did a grocery shop and beer run for the week. I bought things like loaves of bread, blocks of cheese, whole chickens, and salted pork. I also bought a case of beer and an armful of hard cider. That day was full of optimism; it sounded too good to be true that I got to drink all week and eat like that for an assignment!

I regretted that in about three days.

General Washington’s “Rules of Civility” were, at times, almost impossible to implement in today’s world. One rule stated the position to stand next to your superior when you are walking and having a conversation and when and how you were allowed to contribute to that conversation. Rules that did not apply to me, mainly because I never found myself in a position where I was walking and talking to someone who was superior, like a professor.

Other that that the rules were fairly easy to follow; most of them were drilled into me since I was five. Things like put your napkin on your lap, don’t chew with your mouth full, don’t talk about people when they’re not there, and don’t tell a story if you don’t have the full story.

Others posed a much larger challenge. Interestingly enough, the ones I had trouble with tended to be in regards to the body. Rules like keep your feet firmly planted and don’t cross them, don’t touch your beard, or don’t lift one eyebrow higher than the other. I learned this week that I touch my beard way too much and move my feet far too often. It took about four days until those habits started to fade out, but it was not without constant reminder to myself.

An American colonial kitchen. From "A Brief History of the United States" by Joel Dorman Steele and Esther Baker Steele, 1885. Public Domain (Source: Wikimedia)

Eating was probably the most difficult element of revolutionary life to adjust too. And adjust I did not. Most mornings my breakfast consisted of an apple and a hard cider. Lunch was bread, cheese, and beer. And dinner was meat, pork or chicken, and beer or rum.

Rum was never directly mentioned, but maybe I was a sailor who brought it back from the Caribbean. The key is to have fun with it.

The food started out great, it was delicious and it was all washed down with alcohol. However, after a couple of days I was craving a bell pepper and I started feeling greasy and bloated.

I did, however, cook the food in an oven. I tried to be as accurate as possible, but I simply did not have a wood stove to cook on. After I made it over the half way point, the repetitive diet and salted pork started tasting delicious again. Around day five it didn’t feel as though my diet was any different than it ever was.

Food, which I thought would be the biggest barrier, proved to be relative easy. Easier than not touching my beard or hair.

The alcohol, on the other hand, was a challenge.

I underestimated the cumulative effect of a week of casual day drinks, and the occasional night cap. The rules essentially said no water, so in the morning it was hard cider. And then I had to go to class. Naturally, I could not drive and accepted the bus as a substitute for a horse and buggy.

About the time I got home I found that I was tired, tipsy, and in no position to do readings. The solution: another beer. I have not heard yet if my seminar participation was inspired or sloppy, but it was historically accurate.

The part that surprised me the most about my week of historical living was how easy it was for me to not use electricity. I was lucky, in that I had no papers due and did not have to do any research for courses. In seminars that I had to get readings online, I had my roommate print them out and give them to me. I used no artificial lights, no cell phone, no laptop, no Xbox, nor anything related.

I bought about fifty candles from Dollarama the day before I began, and burned through forty-nine of them. I knew that one candle would not be enough for my room to be illuminated enough to function, but I assumed two would do the trick. I burned ten candles at a time. I also learned that candles in front of a mirror produces more light, something that was probably common knowledge back then.

As far as passing the time, I mostly read. I did all of my seminar readings, all of my lecture readings, and read three novels. I also messed around with some doodling and writing.

Everything said and done, I had a blast with no electricity. Of course, I was dying to watch a movie. However, I held strong and did not use any electricity whatsoever. The constant drinking probably helped. I also found that, without trying, I was usually asleep by around ten every night and awake around seven in the morning. A feat I thought impossible two weeks ago.

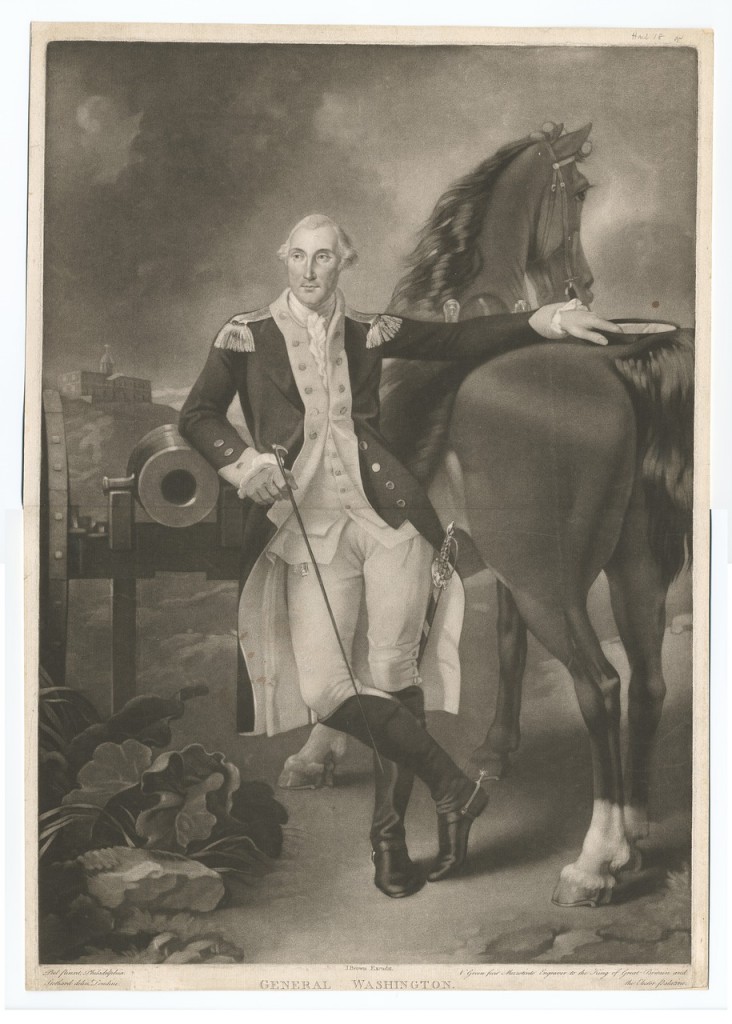

Washington's entry into New York: on the evacuation of the city by the British, Nov. 25th. 1783. Currier & Ives. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. (Source: Wikimedia).

My week of living as a soldier in the Revolutionary War was informative. Obviously I missed the horrendous parts, like war. But I ate, drank, and behaved like a man from the eighteenth century. George Washington’s “Rules of Civility” more or less translated into modern day manners, though we are uncultured compared to the rules he wrote when he was sixteen.

The diet and fluid intake was hard on my body, but I can understand how the body adapts to it and it was certainly favorable to dysentery.

And the technological aspect is one in which I am jealous of the era. I conversed with people more, and I learned much more in one week than I normally would have. I may not volunteer to live like a Revolutionary soldier again, but I do feel as though these past seven days has taught me, to a limited degree, what life was like in America in the late 1700’s.

And, given how drunk, or tipsy, I was on a regular basis, it is a wonder they managed to accomplish anything, let alone build a new empire.