Liz Clarke in Brock University’s Department of Communication, Popular Culture and Film sheds light on a forgotten history of women and silent war films in her new book.

Liz Clarke in Brock University’s Department of Communication, Popular Culture and Film sheds light on a forgotten history of women and silent war films in her new book.A new book from Liz Clarke explores an area the field of film studies has been largely silent on — until now.

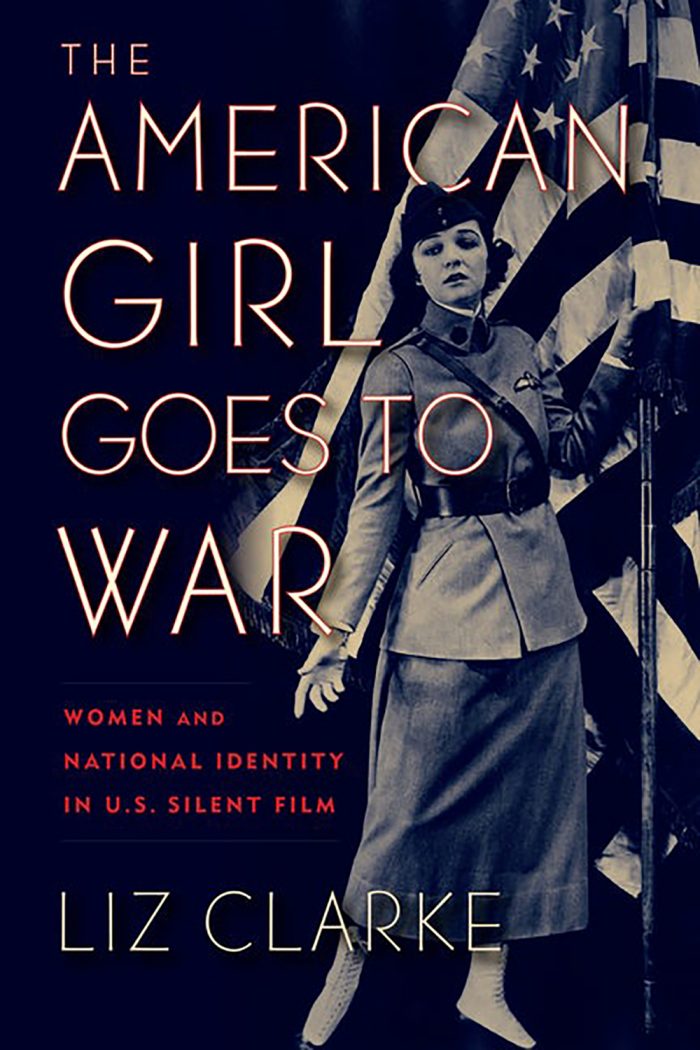

In The American Girl Goes to War, published by Rutgers University Press on Jan. 14, the Assistant Professor in Brock University’s Department of Communication, Popular Culture and Film shares an untold history and analysis of women and war in silent films between 1908 and 1919.

Clarke examines films depicting various armed conflicts in American history, from the Revolutionary War through to a push for military preparations prior to the American entry into the First World War. Of the 500 films she set out to analyze, more than half are set in the Civil War, then a 50-year-old conflict, with white women protagonists often bridging gaps between the two sides and helping to heal a divided nation.

The book grows out of Clarke’s PhD dissertation work, which began as a study of masculinity in war movies. But as she dug into trade journal publications of that era seeking titles and plot summaries and later visited silent film archives at the Library of Congress, the George Eastman House museum and the Museum of Modern Art, she made a surprising discovery.

The American Girl Goes to War is available to order from Rutgers University Press.

Of the 500 or so silent films about war she wanted to investigate, only about 50 survived. And of those 50, a huge proportion featured a female protagonist.

Whether acting as spies feeding key intelligence to George Washington or patriots donning male soldiers’ uniforms to serve American interests, women played key roles in so many of the films that Clarke had to refocus her dissertation to account for the discovery.

“This is why I’ve fully embraced the field of feminist film history,” says Clarke. “I came to it not because I was a feminist first and wanted to find a project to fit with that ideology, but because the evidence showed me that films of that decade were made by women, made for women and made about women in ways that we as scholars haven’t tackled yet.”

Clarke says that film prints that have lasted for 100 years are typically those that were most popular with audiences, because the more prints there were in circulation, the greater the chance that one will exist in an archive or collection somewhere. And yet, many of the films in the book have rarely been discussed.

“Films that have been restored and made widely available as DVD releases, especially the war movies, are predominantly the traditional types that are about male heroics, because that fits in with our expectations of the genre as it evolved in the 1920s,” says Clarke. “There’s a big difference between what survives but sits collecting dust in an archive versus what is made available for students and popular audiences.”

It’s an erasure of female participation in the industry that extends to female filmmakers, as well, which is where Clarke’s research is now focused.

“Part of the assumption is that the film industry has always been structured to exclude women, but if we look back to the early origins of Hollywood, there are all kinds of female directors, cinematographers, editors and writers,” says Clarke. “So, the question is actually why did Hollywood come to exclude women, and why has film history excluded these women?”

Clarke says that many silent films have become more widely available thanks to digitization projects and online platforms, but until the canon changes, they may be underutilized. To this end, she is now collaborating on an edited volume that will feature essays on lesser-known films so that anyone hoping to teach them might have a resource.

“It’s a book about teaching silent film featuring short essays that could be assigned to students if you wanted to choose to teach a film that is not canonical and hasn’t been written about as much as the more traditional titles,” she says. “There are so many fascinating and incredibly diverse films that have become available to screen for students that can allow them to see that the traditional film history narrative that it was an art form made by men, and for the most part white men, was actually not the case.”