Information on Head Injury

ABI

An acquired brain injury (ABI) is a disruption of normal brain functioning

resulting most often from a sudden traumatic event and can induce

permanent problems ranging from motor control to attention and memory

(Banich, 2004). Although ABI is given great attention from an acute

medical perspective far less consideration is given to the longer

lasting neuropsychological effects (Cassidy et al., 2004). The problems

following an ABI can be crippling to the survivors and their families,

but more knowledge may provide insights that can be used to construct

workable solutions (Temkin, Corrigan, Dikmen, & Machamer, 2009).

TBI

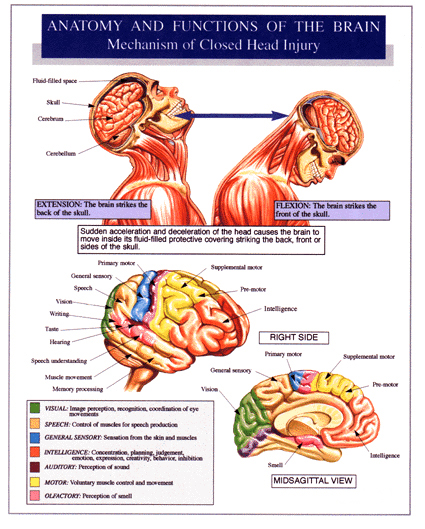

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an acquired brain injury resulting

from acceleration-deceleration forces and/or trauma and can result

from open or closed head injuries (Iverson & Lange, 2009). These

injuries represent a significant proportion of trauma admissions

in Canada as well as in the USA. There are an estimated 120, 000

and 1.5 million TBIs sustained annually in both countries respectively

(Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2006; Mooney, Speed, &

Sheppard, 2005; Iverson & Lange, 2009). TBI is an injury which affects

all ages but particularly adolescents and elderly are at risk (Canadian

Institutes of Health Research, 2006).

TBIs are classified along a spectrum ranging from mild to catastrophic.

The Glasgow Coma Scale and durations of unconsciousness and memory loss following the trauma are most

often used to categorize the injury (Iverson and Lange, 2009). At the lowest end of the traumatic brain injury

scale is where mild is found, the most prevalent classification comprising approximately 70-90% of TBIs (

McKinlay, Grace, Horwood, Fergusson, Ridder, & Macfarlane, 2008).

Problems associated with traumatic brain injury vary depending on the severity but often

include: motor impairments/disorders, deficits in balance and experience of dizziness,

visual impairments, cranial nerve impairments, headaches, sexual dysfunction, fatigue and sleep disturbance,

depression/anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, personality changes, and lack of awareness

(Ashman, Gordon, Cantor, & Hibbard, 2006; Iverson and Lange, 2009). The appearance and persistence

of these neurological or neuropsychiatric problems follows the gradient of the classification spectrum.

Research has indicated that there are significant alterations in cognitive performance as a result of even mild TBI

(Kwok, Lee, Leung, & Poon, 2008). The prevalence and consequences of mild TBI

creates a clear and obvious need for greater understanding.

MTBI

Mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) is formally defined by Kay and colleagues

(1993) as a physiological disruption of brain function which has any loss of

consciousness, memory, or alteration in mental state at time of accident. The resulting

effects of MTBI although rarely life threatening are nonetheless health concerns which

may persist for months or longer. They also create a cost for the individual and medical

providers alike (Kraus, Schaffer, Ayers, Stenehjem, Shen, & Afifi, 2005).

|

|

References

Ashman, T. A., Gordon, W. A., Cantor,

J. B., & Hibbard, M. R. (2006). Neurobehavioral consequences

of traumatic brain injury. The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine,

73(7), 999-1005.

Banich, M. T. (2004). Cognitive

neuroscience and Neuropsychology (2nd Ed.). Boston, MA:

Houghton Mifflin Company.

Canadian Institutes of Health

Research (2006). Head injuries in Canada: A decade of change

(1994 - 1995 to 2003 - 2004)-Analysis in Brief. Canada: Canadian

Institutes of Health Research. Retrieved from www.cihr.ca

June, 2011.

Cassidy, J. D., Carroll, L. J.,

Peloso, P. M., Borg, J., von Holst, H., Holm, L., et al. (2004).

Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of mild traumatic brain

injury: Results of the WHO collaborating centre task force on

mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of rehabilitation Medicine,

43, 28-60.

Iverson, G. L., & Lange, R. T.

(2009). Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. In M. R.

Schoenberg and J. G. Scott (Eds.), The black book of neuropsychology:

A syndrome based approach. New York: Springer.

Kay, T., Harrington, D. E., Adams,

R., Anderson, T., Berrol, S., Cicerone, K., et al. (1993). Mild

Traumatic Brain Injury Committee, American Congress of Rehabilitation

Medicine, Head Injury Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group.

Defmition of mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head

Trauma Rehabilitation,8 (3), 86-87.

Kraus, J., Schaffer, K., Ayers,

K., Stenehjem, J., Shen, H., & Afifi, A. A. (2005). Physical

complaints, medical service use, and social and employment changes

following mild traumatic brain injury: A 6-month longitudinal

study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 20(3), 239-256.

Kwok, F. Y., Lee, T. M. C., Leung,

C. H. S., & Poon, W. S. (2008). Changes of cognitive functioning

following mild traumatic brain injury over a 3-month period.

Brain Injury, 22(10), 740-751.

McKinlay, A., Grace, R. C., Horwood,

L. J., Fergusson, D. M., Ridder, E. M., & Macfarlane, M. R.

(2008). Prevalence of traumatic brain injury among children,

adolescents and young adults: Prospective evidence from a birth

cohort. Brain Injury, 22(2), 175-181.

Mooney, G., Speed, J., & Sheppard,

S. (2005). Factors related to recovery after mild traumatic

brain injury. Brain Injury, 19(12), 975-987.

Temkin, N. R., Corrigan, J. D.,

Dikmen, S. S., & Machamer, J. (2009). Social functioning after

traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation,

24(6), 460-467.

|

|