Psychology

Chapter 8: Imagination

James Rowland Angell

Table of Contents | Next | Previous

General Psychophysical Account of Re-presentation.-- In the last chapter we saw that even in those psychophysical processes where the sense organs were most obviously engaged, the effects of past experience were very conspicuous. This fact will suggest at once the probable difficulty of establishing any absolute line of demarcation between processes of perception and those which, in common untechnical. language, we call memory and imagination. We shall find as we go on that this difficulty is greater rather than less than our first impressions would indicate, and it will be well to come to the matter with the understanding that we are examining various stages in the development of a common process, rather than with any idea of meeting entirely separate and distinct kinds of mental activity. We called attention to this same point at the outset of our analysis of the cognitive functions.

Our study of habit brought out clearly the strong tendency of the nervous system to repeat again and again any action with which it has once successfully responded to a stimulus. This tendency is peculiarly prominent in the action of the brain as distinguished from the lower nervous centres and the peripheral nerves. The undoubted retention by the nervous organism of the modifications impressed upon it by the impact of the physical world, in what we call experience, is commonly designated "organic memory," and forms beyond question the physiological basis of conscious memory. Thus, in perception, as we have just seen, the sensory nerves may bring in excitations of as novel a character as you please, but

(162) the brain insists on responding to these stimulations in ways suggested by its previous experience. That is to say, it repeats in part some previous cerebral action. Similarly, we observe that from time to time thoughts flit through our minds which we have had before. This we may feel confident, from the facts we examined in Chapter II., means a repetition in some fashion of the cortical activities belonging to an earlier experience. Sometimes these thoughts are what we would commonly call memories, i. e., they are thoughts of events in our past lives which we recognise as definitely portraying specific experiences. Sometimes they are what we call creations of fancy and imagination. But even in this case we shall find it difficult to convince our-selves that the materials of which such thoughts are constituted have not come to us, like those of clearly recognised memories, from the store-house of our past lives.

Although we shall postpone the detailed examination of memory until the next chapter, and must therefore anticipate somewhat the full proof of our assertion, we may lay down the general principle at once, that all psychophysical activity involves a reinstatement, in part at least, of previous psychophysical processes. Stated in terms of mental life alone, and reading the principle forward instead of backward, it would stand thus: all the conscious processes of an individual enter as factors into the determination of his subsequent conscious activities. With this general conception in mind, we have now to analyse the special form of representation known as imagination.

General Definition of Imagination.--The term imagination, in its ordinary use, is apt to suggest the fanciful and the unreal, the poetic and the purely aesthetic. We speak in this way of great poems as " works of imagination." We describe certain persons as of imaginative temperament when they are subject to romantic Rights of fancy, etc. These implications are of course properly a part of the meaning of the

(163) word, when employed in its usual untechnical sense. But the psychologist uses the term in a broader way than this. In the preceding chapter we discussed the consciousness of objects present to the senses. Imagination, in the psychologist's meaning, might be called the consciousness of objects not present to sense. Thus, we can imagine a star which we do not see; we can imagine a melody which we do not hear, an odour which we do not actually smell, etc. Stated in the more usual way, imagination consists in the reinstatement of previous sensory excitations. Speaking broadly, both perception and imagination would evidently involve the consciousness of objects, and their primary distinction from one another would be found in the physiological fact that one arises immediately from a sense organ stimulation, while the other does not. The principal psychical difference we pointed out in a previous chapter. The perceptual consciousness, which is peripherally originated, is almost invariably more vivid, enduring, and distinct than the centrally initiated process of imagination, and seems to us somehow more definitely "given" to us, to be more coercive. But the similarity of the one process to the other is quite as obvious, and quite as important, as their difference. The stuff, so to speak, out of which visual imagination is made is qualitatively the same kind of material as that out of which visual perception is made. Indeed, when we describe imagination as a consciousness of objects, we have already suggested that which is really the fact, i. e., that all imagination is based in one way or another upon previous perceptual activities, and consequently the psychical material which we meet in imagination is all of a piece with the material which perception brings to ,us, and altogether like it, save that in imagination the fabric is often much faded and sometimes much cut up and pieced. So far as we approximate pure sensations in sense experience. so far do we have images reinstating approximately pure qualities as distinct from objects. Images of

(164) warmth, for instance, may have in them relatively little suggestion of objective character.

Analysis of Imagination. (A) Content. -- If we were to ask a dozen persons to think of a rose for a few moments, and then relate for us the ideas which had passed through their minds, we should find that some of them had at once secured a mental picture of the rose in which the colour and the form were represented with considerable accuracy and detail. These persons evidently got visual images of the rose. Others would have found that the word "rose" came at once into mind, followed by other words such as " American Beauty," " red," " bud," etc. These words would, perhaps, have been heard mentally, and together with this mental hearing the more acute observers would report for us a similar consciousness of the sensations of movement which arise from the throat and lips when one is enunciating the words. This group of persons would have experienced auditory and motor imagery. Still others would report a faint consciousness of the odour of the rose, which involves olfactory imagery; and a few might tell us that they fancied they got tactual images, such as would arise from the thought of touching the soft petals, it might occur, although we should find this result rare, that some individual would report all of these images as passing through his mind in sequence.

It has been asserted that we have no genuine motor, or kinaesthetic, images, because every attempt to think of a movement results in our actually making the movement in a rudimentary way; so that we get a kinaesthetic sensation instead of a kinaesthetic image. There can be no doubt that this is often the case; e. g., the effort to think how the word "back" sounds will by most persons be found to be accompanied by a definite feeling in the tongue and throat. Moreover, there can be no doubt that the normal procedure is for every kinaesthetic ideational excitement to produce movement. This is only less immediately true of ideational excitement of

(165) other kinds. Meantime, there seems to be no reason in the nature of the case why we may not have kinaesthetic images in a form definitely distinguishable from the kinaesthetic sensations. to which they may lead; and many observers insist that their introspection verifies the reality of these images.

According to the commonly accepted doctrine there are, theoretically at least, as many kinds of images as there are sense organs. If our experiment be amplified and a large number of persons be submitted to it, we shall find that it is much easier for most persons to secure with confidence accurate and reliable images of the visual, auditory, and motor varieties than it is to secure those of the gustatory, thermal, tactual, and olfactory types. Later on we shall inquire into the probable reason for this difference. Moreover, we should find in the same way, if we gathered statistics upon the subject as others have done, that many persons, even though they can with sufficient effort command various forms of images, actually have their imagination in its ordinary use dominated by some one or two forms. From this observation has arisen the recognition of mental "types," and currency has been given to the division into " audiles," " tactiles," " motiles," etc.

These types are, as we have just pointed out, seldom or never absolutely exclusive of one another. But they indicate the prevalent form of mental material. With most of us there appears to be a relatively good representation of several forms, especially the visual, auditory, tactual, and motor. In any event we find that specific images of one kind or another always constitute the content, the material, of imagination.

Image and Idea. -- It may serve to clarify the terminology employed from this point on, if we pause to distinguish tentatively between the terms image and idea. So far as we have in mind the sensuous content of a thought, e. g., its visual or

(166) auditory character, we use the term image. So far as we wish to emphasise in addition to, or in distinction from, this fact of sensuous constitution the purport, significance, or meaning of the image, we use the term idea. Images and ideas do not refer to two different states of consciousness, but to one and the same state, looked at now from the side of sensory character and antecedents, now from the side of meaning. The matter will be discussed more fully in our analysis of the concept.

It should also be reiterated that in speaking of images as though they were distinct mental events ' we do not mean to imply that the image constitutes the whole of consciousness at any given moment; nor that thought is made up of disconnected bits of stuff called images. We are simply indulging the kind of abstraction in which we frankly announced our purpose to indulge. Images merely represent, on the cognitive side, the more substantive moments in the onward flow of consciousness. They rise by indiscernible gradations out of antecedent conscious processes, and fade away into their successors without a vestige of abrupt separation. Moreover, any given image is merged in a setting of sensory processes representing the momentary bodily conditions, attitude, etc., of which we made mention in discussing the physiological accompaniments of attention.

(B) Mode of Operation of Imagination.-- If we watch the play of our images under different conditions, we observe, regardless of the sense department to which they belong, certain marked peculiarities which evidently call for separate classification of some kind. In dreams, for example, there often appears to be the utmost chaos in the fashion in which the images succeed one another; and when we have regard to their composition and character, they occasionally seem to be utterly -novel and bizarre inventions, the like of which we have never known in waking experience. The hobgoblin's of nightmares, with their inconsequential torments, are illus-

(167)-trations of this sort of thing. On the other hand, in revery, our minds ocasionally (sic) wander off amid trains of images which are coherent in their relations to one another, and which evidently spring from recognisable experiences, of which they are in a measure faithful representations. Thus, the recollections of a journey may pass through our minds, diversified by excursions into connected fields of thought suggested by the various incidents of the trip. Can it be that these two forms of imagination are really identical? Is the process which brings back to mind the recollection of the sound of the multiplication table one and the same in kind with that which leads to the sudden perfection of an invention, or the inspiration of a fine verse? To answer this question in even a provisional way requires a closer examination of these two forms of imagination, to which psychologists have assigned the names " reproductive " and " productive " respectively.

Reproductive Imagination.-- Reproductive imagination consists in the representation of perceptions, or images, which have previously appeared in our consciousness. Thus, I may close my eyes and obtain a visual image of the desk at which I am writing. Such an image would illustrate what psychologists mean by reproductive imagery, inasmuch as my imagination would in this case simply repeat, or reinstate, some conscious experience which has previously been present in my mind. Evidently at this rate the great mass of the events which we are able to remember would be recalled by means of reproductive imagination. Our ordinary memory processes would be instances of reproductive imagination, or, as it is sometimes called, re-presentation.

Productive Imagination.-- Productive imagination on the other hand involves the appearance in consciousness of images which have never before entered the mind in their present order and form. Thus, the visual image of an eightlegged dog might be called up, although it is reasonably cer-

(168) -tain that most of us have never seen such an animal, even a picture of it. Such an image would illustrate, nor rough way, what is meant by productive, or constructive, imagination.

Now it is a favourite conceit of the untutored mind to suppose that it is possible mentally to create absolutely new materials for ideas, that it is possible to burst over the bounds of one's past experience and beget thoughts which are wholly novel. This is a flattering delusion which a little reflection will effectually dispel, although there is a distorted truth underlying the vanity of the belief.

In the case of the eight-legged dog it is clear that, although we may never have encountered just such a creature in any of our adventures, the superfluous legs with which we have endowed him, which constitute his sole claim to novelty, are merely as legs familiar items in every experience with the canine breed.

The productivity of our imagination consists, therefore, in the modest feat of putting together in a new way ma. terials of a thoroughly familiar kind. There is, and can be, no question of our having originated de novo fresh elements of the psychical imagery. We shall find a similar thing true of any instance we might examine in which a genius has created a new poem, a new statue, a new melody or symphony, a new machine, or a new commercial process. In each and every case, startling as is the result, and novel as may be the combination in its entirety, the elements which have been thus ingeniously juxtaposed are all of them drawn in one way or another from the richness of the individual's previous experience. Productive imagination is productive, therefore, only within the limits set by the possibility of combining in new ways the materials of past states of consciousness. But such limitations, be it said, afford scope for an amount of originality and creative fertility which far surpass any human accomplishment thus far recorded.

(169)

Relation of Productive to Reproductive Imagination. - It appears at once from the foregoing statement that in one sense all productive imagination is really reproductive; and that in consequence we have in the last analysis only one form of relation obtaining between our present imagery and our previous consciousness. Strictly speaking this is undoubtedly true. The differences which attract our attention to the seemingly distinct modes of imagination are primarily differences in the degree to which any given image, or any sequence of images, actually correspond to the entirety of some antecedent conscious event in our lives. When the correspondence is obvious, we think of the imagery as reproductive. When it is not, we are likely to credit it with creative characteristics, and justly so, within the limits which we have designated. It only remains to notice one peculiarity about reproductive imagery which serves to modify some what the purport of our conclusion.

It is altogether problematical whether any image is ever in a thorough-going way a mere reinstatement, or repetition, of a previous perception or image. I may to-day, for example, think by means of an auditory-motor image of the word psychology; I may do exactly the same thing to-morrow, and I shall then speak of having had the same image on two occasions.. But it is clear in the first place that I cannot prove the two images to be really alike; for I can never get them side by side in my mind for comparison. When one is there, the other has gone, or has not yet arrived, as the case may be. Furthermore, if we turn to the considerations which we canvassed when we discussed the operations of the cerebral cortex, we shall find reason for thinking that no two images ever can be quite alike. For we saw that our consciousness, in which these images appear, and of which they are a part, apparently runs parallel with the brain activities; and it is quite certain that the brain, through its constant change of structure and tension, is never twice in precisely

(170) the same condition; and consequently is never in a position to lead twice to the same excitation of consciousness.

On the whole, then, it is perhaps nearer the truth to say that all imagination is productive, rather than reproductive. When we speak of having bad the same image on several occasions, what we really mean is that we have had in this way images which we employed to refer to the same object. They have thus served our purpose quite as efficiently as they could have done by being actual copies, the one of the other.

The same thing is more obviously true as regards any image which purports to represent a perception. Functionally, as regards what it does for us, what it symbolises, it really does reinstate the perception; but it is not on this account necessarily an exact copy of the perception. The distinction between reproductive and productive imagination must not, therefore, be conceived of as resting on ultimate differences. It marks a practical distinction, which is useful in enabling us to indicate significant variations in the operations of our imagery.

Successive Association of Images. -- This is a convenient point at which to consider the principles controlling the sequence of our images, as they pass through the mind. The so-called law of association, which has played historically so important a part in psychology, undertakes to formulate the facts under a single general principle, i. e., the principle of habit. We have mentioned in an earlier chapter the phenomenon known as simultaneous association. The process which we are to examine at this juncture is designated successive association.

The law of association asserts that whenever two images, or ideas, have been at any time juxtaposed in the mind, there is a tendency, if the first of them recurs, for the other to come with it. Furthermore, the law asserts that so far as concerns the sequence of ideationally aroused imagery, no

(171) image ever comes into the foreground of consciousness unless it has been in some way connected with its immediate predecessor. The order of our thoughts is, in short, determined by our antecedent experience.

It is clear to the most casual reflection that this principle, if true, must operate under a number of definite limitations. We know, for example, that a given idea comes into the mind on one day with a certain set of accompaniments, and on another occasion presents itself with a wholly different escort.

How is such a variation to be accounted for? If we follow James in formulating the relation in brain terms, we may say that the liability of any special cortical activity, such as x, connected with the thought x1, to arouse any other cortical activity, such as y, connected with the thought y1, is proportional to the permeability of the pathway joining the brain areas involved in the production of x and y, as compared with the permeability of all the other pathways leading from the brain area involved in x to other regions of the cortex. (Figure 55.) Now this permeability must be largely a function of previous use; that is to say, pathways which have by repeated employment become deep-cut in the brain tissues will, other things equal, be most pervious. Stated in purely psychological terms, this will mean that the oftener any two ideas have actually been associated with one another, the more chance there will be that if the first one appears in consciousness the second one will accompany it.

Among the many factors which must affect this permeability of the brain paths, three important ones are easily discernible. These are the frequency, intensity, and recency of associative connection. Images which have been frequently associated evidently must be connected with neural activities which will tend, if once aroused, to react in the regular habitual way. Images which have been connected with one another in some vivid experience, will be connected with in-

(172)-tense

neural activities, whose modifications of the brain tissues will therefore tend to be

relatively deep and permanent. In this case, again, we may look, under the general

operation of the principle of habit, for practically the whole of the par. ticular

psychophysical activity to be called out, provided anything starts up the first step in

the process. Similarly, if two images have been recently associated, the pathways joining

the brain tracts responsible for their accompanying cortical activities are likely to be

open; and the recurrence of the first image may readily bring with it the reinstatement of

the second. When we take into account the enormous number of our perceptual experiences

and the varied richness which they present, we see at once that the number of possible

associates which the idea of any one of these experiences may possess is extremely large.

(172)-tense

neural activities, whose modifications of the brain tissues will therefore tend to be

relatively deep and permanent. In this case, again, we may look, under the general

operation of the principle of habit, for practically the whole of the par. ticular

psychophysical activity to be called out, provided anything starts up the first step in

the process. Similarly, if two images have been recently associated, the pathways joining

the brain tracts responsible for their accompanying cortical activities are likely to be

open; and the recurrence of the first image may readily bring with it the reinstatement of

the second. When we take into account the enormous number of our perceptual experiences

and the varied richness which they present, we see at once that the number of possible

associates which the idea of any one of these experiences may possess is extremely large.

If the idea 7 times 9 pops into my head, it is promptly followed by the idea 63. If, however, 4 times 9 comes to my mind, the next idea is 36. In both cases the idea 9 is present, but the subsequent associate depends upon the special concomitant with which the idea 9 is combined in the antecedent thought process. In a similar fashion our memory of special words in poetry depends upon the total mass of verbal associates with which they are surrounded. The word " mirth " occurs

(173) in two of the following lines, and taken alone might suggest either of the following groups of words. Taken with its predecessors it rarely fails to awaken its correct consequents.

"And, if I give thee honour due,

Mirth, admit me of thy crew,These delights if thou canst give,

Mirth, with thee I mean to live."

Even if no factors were operative in the modification of the general principle of association, other than those we have already mentioned, we should find it practically impossible ever to predict with confidence what particular idea would come to our mind at any special moment. The law of association is not, therefore, a principle of prediction, but simply a formula for rendering intelligible in a schematic way the nature of the influences which control the order of our thoughts.

It remains to remark one further factor of equal importance with those already mentioned in its effect in determining what associates shall recur with an idea at any given time. This is our momentary interest, the prevailing tendency of our attention. If our minds are dominantly engaged upon any line of thought, as when we are wrapt up in some absorbing problem, or plunged in some profound emotion, the ideas which flood our minds are almost wholly such as sustain intimate relations to the matter in hand. When we are overcome by sorrow all our thoughts centre about our grief. No other thoughts can gain a hearing from us. And the same thing is true in varying degree of any intense mental preoccupation. We see, then, that the principle of association, or cortical habit, is modified, not only by the changing relations among the factors of past experience already mentioned, e. g., such as frequency and recency, but also by the present psychophysical conditions reflected in such things as our attention and interest. This means, so far as concerns the brain, that those pathways are normally

(174) most pervious which connect most intimately with the entire mass of ongoing brain processes. The astonishing vagaries of dream consciousness illustrate what may occur when all dominating purpose is removed and the associative machinerv is allowed to run wild and uncontrolled.

Psychologists have been interested in various types of association, which they have called association by contiguity, association by similarity, contrast, etc. Association by contiguity is essentially identical with the process of which we have been speaking heretofore. A suggests B, not because of any internal connection, but because the two have often been contiguous to one another. This contiguity is originally perceptual in character. The objects are actually present too-ether to the physical senses. All association is primarily dependent upon the contiguity of perceptual objects, as will be readily apprehended when the dependency of images upon perception is recalled.

Ideas apparently follow one another at times, however, which could not have been previously experienced together, and in certain of these cases we remark at once that the two things suggested by the ideas are similar, contain an internal element of connection. We meet a total stranger, perhaps, and instantly observe the similarity to some absent friend. Poetry owes much of its witchery and charm to the delicate and unusual resemblances which the poet detects for us, as when he says:

"So gladly, from the songs of modern speech

Men turn, . . . .

And through the music of the languid hours,

They hear, like ocean on a Western beach

The surge and thunder of the Odyssey."

All the more conspicuous forms of genius seem highly endowed with this type of association, which is undoubtedly a genuine form of mental activity. We shall err only if we

(175) suppose the similarity to be somehow the cause of the association. As a matter of fact we always observe the similarity after the association has occurred, not before, as should be the case if it were strictly speaking a cause. James suggests, and this seems as plausible as anything yet proposed, that the brain activities involved in thoughts of two similar things are in part identical, and that consequently we have in their suggestion of one another a further instance of the principle of cortical habit. (Figure 56.) The brain processes x and y, having the similar thoughts x1 and y1 as their concomitants,

possess a common brain activity z. When x is active, there is thus a chance that the excitation of z may stir up y, to which z also belongs. Oftentimes the elements of likeness between two objects are several, as in cases of personal resemblance. On other occasions the resemblance may reduce to a single element. But the principle of explanation is the same in either case.

Association by contrast is really a modification of the contiguity and similarity classes. Things are not felt as contrasting unless they have some element of likeness, and to feel this likeness and difference commonly involves experiencing them together, as when we come to remark the contrast of black with white.

(176)

Miss Calkins has pointed out that in certain associative sequences the image which comes into the mind entirely displaces the one which previously held sway. She calls this type of case desistent association. In other cases, however, a part only of the departing image is lost, the rest being taken up into the new image which succeeds it. This she calls persistent association. This analysis seems to touch upon a real distinction, but it clearly introduces no basal alteration into the general nature of the principle controlling the ideational sequences.

Genesis and Function of Imagery.-- The best clue 10 a correct understanding of the function of the image is to be gained, as in the case of all organic activities, when possible, by examining the conditions of its genesis, its appearance upon the field of psychophysical processes.

In several of the preceding chapters we have examined the evidence underlying our thesis, that consciousness appears at those points where the purely physiological mechanisms of the organism prove inadequate to cope with the requirements of its life. We have seen how the organism is endowed at birth with certain established sensory-motor neural pathways, by means of which it is enabled to respond with appropriate movements to certain primitive kinds of stimuli. We have also seen how, at the places where these responses are found insufficient, sensory consciousness appears; and we find, first, vague sensation processes, and then crude perception. We have also noticed how attention, working upon this crude perceptual matrix, succeeds in differentiating it into the multitude of qualities and objects which constitute the world of the adult. In seeking to detect the appearance and the function of imagery, we must remember, then, that from the outset of life organic activities are in progress and the sensory-motor activities in particular are in full swing. Each sensory stimulus is producing movements, which in turn are productive of fresh sensations. It is out from such a

(177) cycle of onward moving coordinations as these, therefore, that the image emerges; and if our previous hypothesis is really adequate to all the facts, it must be that the image is called forth by some need of the organism which the processes that we have already described are incompetent to satisfy. This is undoubtedly the case, and we have only to observe the evident limitations in the capacities of the perceptual processes, taken by themselves, to discern certain of the functions which our images subserve.

Perception enables its possessor to register in consciousness the particular object momentarily presented to the senses. But if consciousness never advanced beyond the merely perceptual stage, it is not apparent that it could serve to develop systematised and intelligent movements of response to environmental demands and opportunities. We should always live in the immediate present, and our minds could consciously look neither backward nor forward. Now it is in the image that we find the psychical mechanism for accomplishing both these highly important functions.

If an organism is to be in the fullest possible measure master of its own fate, it must be able to bring to bear upon the incitations of any particular stimulus all the information which its total experience will permit. Its response must thus represent, not only the intrinsic tendency to overt action, which belongs to the stimulus itself, but it must also represent and express all the tendencies to movement which remain as the result of yielding to previous incitations. Unless there be some organic arrangement of this kind, by means of which each act may represent with some adequacy the product of all related experiences in the past, one's actions would be as purely reflex, or as purely haphazard, as those of the least developed creatures. It is obvious that mere perception-although, as we have noticed, it does embody in a certain way the outcome of antecedent consciousness-does not in any sufficient manner provide for such a focussing of

(178) one's past experiences upon the selection of specific acts, as is demanded by the best accommodatory responses. Without the image we might make many appropriate reactions, but we should also make many more inappropriate ones than we now do, and any development of intelligence, in the proper sense of the word, would be impossible.[1]

The image is, then, the primary psychical process by means of which we bring into mind at need the experiences of the past. It is also the means by which we forecast the future. If I wish to remember what I read yesterday, I accomplish it by summoning images which represent the experience at issue. If I wish to decide which of several lines of conduct I had. best pursue, or which of several possible acts my enemy is likely to hit upon, I do it in either case by the use of images, which serve me in my tentative prognostication. These images may of course be of any variety, but in my own case they are likely to be largely visual-images of objects, or scenes-and auditory-motor images of words, for my own thinking goes on largely in these terms. The image thus affords us the method by which we shake off the shackles of the world of objects immediately present to sense, and secure the freedom to overstep the limits of space and time as our fancy or our necessity, may dictate.

If we have correctly diagnosed the chief function of our imagery we may be certain that it makes its first appearance at a very early stage in the conscious life of the human being. For obvious reasons it is not possible to designate the precise

(179) moment in the unfolding Of the life of tile mind at which the image is clearly and distinctly differentiated from the

vague matrix of sensory-motor activities which we have seen characterising the first experiences of the child. But we may be confident that it is beginning to emerge in some sense departments, whenever we see unmistakable signs of volition, say at about the twelfth week in most children; and there is no reason why it may not be present, in a crude, indefinite I way, from the beginning of extra-uterine life.

The Training of Imagery.-- The development of imagery in the main runs parallel with that of perception, with which, as we saw in the previous chapter, it is very intimately connected. It holds to reason, without any elaborate justification, that if any sense organ is allowed to go unused, or is used infrequently, the imagery belonging to that special sense cannot develop freely. In confirmation of this general assertion we have but to notice that the imagery which most of us find we can command with greatest accuracy and flexibility is that belonging to the perceptual processes with which we are most intimately familiar, i. e., vision, hearing, movement, and touch. Compared with these, our images of temperature, smell, and taste are relatively impoverished. Moreover, children who lose their sight before they are five years old commonly lose all their visual images, thus exhibiting further evidence of the connection of the image with sense organ activity. Nevertheless, we have to admit that we display individual peculiarities and preferences in the kind of imagery which we explained in terms of sense organ activities. The eye and the ear may be used with indifferent frequency and effectiveness, and still the imagery be dominantly of either the visual or auditory kind. Differences of this sort probably rest upon unassignable structural variations, such as those which determine the colour of our eyes.

If we examine the type of development which characterises

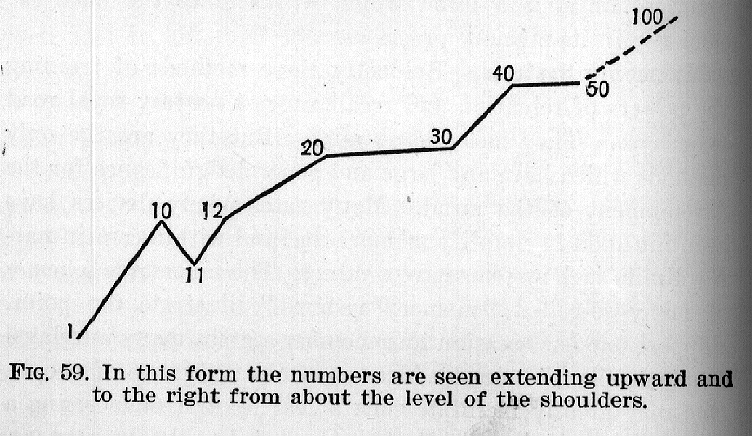

(180) the growth of any special form of imagery, such, for example, as the visual, we shall find that two distinct tendencies are discernible. We find (1) that the number of objects which can be simultaneously visualised increases, and (2) that the vividness, detail, and definiteness of the image increases. It is astonishing to observe bow rapidly this capacity for visualising unfolds in response to a little systematic effort and practice. By devoting to the task a few minutes each day for a week, one may learn to visualise with great detail and remarkable accuracy the form, size, colour, etc., of even large and complex objects, such, for example, as great buildings. Generally at the outset we find that our images are relatively faint, meagre, and unstable; they lack vividness and veracity in colour, detail in form, and appropriate dimensions in size. Images of other varieties, auditory, for instance, are similarly defective at times, and yield as a rule to discipline, with a corresponding form of development.

But after all, the important development of our imagery is not to be found by inquiring for such changes as we thus detect, when we consider it of and by itself apart from its place in the totality of psychophysical activity. The essential thing is the increase in the dexterity with which we employ it, and the growth in the efficiency with which it serves its special purpose in the economy of the organism. We have already commented upon its principal function. It is the psychical device by which we are enabled consciously to focalise upon our acts the lessons of our previous relevant experiences, and through which we forecast the future in the light of the past.

To perform this function with the greatest ease, promptness, and efficiency is the goal toward which the development of our imagery tends, both in those cases where we, as psychologists, purposely bend our efforts in that direction, and also in those cases characterising ordinary practical life, in which our attention is concentrated upon, and

(181) absorbed in, the execution of some act, and for the moment is oblivious to the means employed.

We have already, in an earlier chapter, outlined the general nature of this development, and we need hardly do more here than refer to the significant facts, and cite an instance or two of the process involved. If I wish to express some proposition with the greatest possible force and clearness, I go about it by calling into my mind auditory-motor word images. Clearly I might use other kinds of imagery without affecting the relations which we are now examining. As a matter of fact I generally use, as do most persons under these conditions, auditory and kinaesthetic imagery. From among these word images I select that combination which appeals to my judgment as most appropriate and effective. Evidently the success which I achieve will be in part conditioned by the extent and richness of the images which I am actually able to summon. We speak sometimes of persons possessing a rich vocabulary. In the case of our illustration, my possession of a good vocabulary means, when stated in strictly psychological terms, that I can command a large and effective group of auditory word images.

As a child my imagery of the verbal kind is necessarily circumscribed in amount and phlegmatic in operation. When adult years are reached the amount of the available imagery is ordinarily much augmented, but unless there be discipline in its actual use, it is commonly found that much investment of time and effort is needed in order to secure the best and most expressive terms. The only real and infallible means of training one's imagery for such actual operations is found in the definite use of it, either by writing or speaking. Practice is here, as elsewhere, the one invariable clue to the highest attainable success. The business of such imagery is always to be found in some act, and the only way to develop it and make it reliable and efficient is by working it. For various reasons, which we need not pause to discuss, the possession

(182) of a good vocabulary for writing purposes does not necessarily carry with it a rich vocabulary for speaking; and in less degree the converse is true. One commonly requires separate training for each form of activity, if the best results are to be attained.

When we were discussing the principle of habit we observed that all such coordinations as those which we have just mentioned tend, under the influence of practice, to become essentially automatic; and that consciousness consequently tends to disappear from their control. If this be always the case, the idea is at once suggested that in such a process as is involved in our illustration, i. e., the process of linguistic expression, the same tendency should be in evidence. I believe this to be actually the fact, and I think a little observation will confirm the position. We shall have occasion to examine the question more at length when we discuss later on the relation of language to reasoning, but a word or two may properly be inserted here.

Just in the degree to which our linguistic expression involves thoroughly familiar ideas, and deals with familiar situations, do we find our consciousness of definite imagery vague and indistinct. A student inquires: "What did you mention as the date of the battle of Waterloo?" Instantly, almost without any definite consciousness of what I am about to say, I find I have replied-" 1815." But when the expression is of some relatively unfamiliar idea, when the thought presents the possibility of several discrepant modes of utterance, I promptly become aware of imagery. Not always verbal imagery of course. That consideration is wholly secondary. But imagery of one kind or another I always find when the coordination required cannot be executed in the purely -- or almost purely-habitual manner. If the situations with which we have to cope by means of speech were more widely fixed, instead of being, as they are in fact, relatively unstable and fluid, relatively changeable, I see no reason to doubt that

(183) speech, like walking, might become essentially automatic -- as I believe it to be in part already.

Summarising, then, we may say that all imagery arises oat of perceptual activities, upon which its appearance is, therefore, most immediately dependent; it develops by use in the actual processes of controlling action, and develops its real functions in no other way. This accounts for its appearance in greatest profusion in connection with those sense processes which are most significant for human. life. It tends to drop away after it has served, in the general congeries of consciousness, to establish effective habits. It only remains to add , that while it arises from perception, it also reacts upon perception; for we perceive with fresh vitality those objects, qualities, and relations for which we possess distinct images.